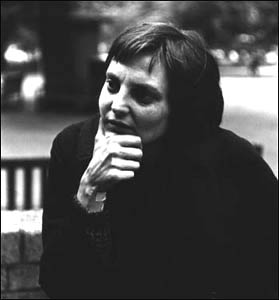

London, ca 1964. Photo JF.

Judgment

I

In her dealings with others, C. had, where it mattered, what I think of as the moral equivalent of perfect pitch. I don’t mean that she was always “fair,” or rational, or dispassionate. She would come home furious with some cop who gave her a parking ticket, even though acknowledging that she was parked illegally or at an expired meter. She intensely disliked phone solicitations for worthy causes when they were made around suppertime. “They know that’s when we’re going to be in,” she would say indignantly. At times her angry comments about some friend would make her sound a bit like a little girl announcing that she was never, ever, going to speak to Mary Lou again—and then next day walking arm-in-arm with her to school.

Where it mattered, though, she seemed to me almost invariably on target. A former schoolmate of mine, surfacing briefly in Halifax, and to my mind a bit irritating still, became for her almost immediately a model of true virtuousness, which I think he was. (Saints are not necessarily bland or easy to get along with.) In Ajijic, when we met a writer of bestselling romances and the quiet friend with whom she was sharing a bungalow for three months, C. rapidly decided that the novelist, whom I myself found entertaining and not insistently egotistical (I mean, she was willing to talk about me as well as about herself) was the less interesting personality of the two. The friend was an artist, and probably not a very good one, but that didn’t come into it for C. What counted was her attitude towards her art, her new environment, and her family back home.

She was quick to detect a certain phoniness, as in the kind of peacenik who she felt had found cost-free ways of being on the side of virtue. But she was also alert to symptoms of unhappiness in people she liked, and she could see through an unprepossessing exterior and put her trust where it was deserved.

Our landlord at Ajijic, a plump, genial, youngish son of the village who spoke fluent if often fractured English, struck me when we first met as being a perfect con-artist, and he did in fact try to put something over on us at the outset. But C. spotted much sooner than I did the shift in his attitude once he decided that we were all right, and he proved to be extraordinarily generous as a landlord, and genuinely concerned that we enjoy our time there.

II

Part of her gift, I think, consisted in her being able to focus on what was in front of her. I myself would decide that so-and-so was pleasant to be with, like our bestselling acquaintance, and that I was not going to look too closely at particulars, or that our landlord was someone who would have to be watched like a hawk in all our business dealings. C. was much more flexible for the most part, though there were a few people whom she couldn’t abide, and one or two whom she hated. For obvious reasons, I won’t name them here, but her friends will know who they were.

She could read signs much more quickly than I could, and she could live with a double or triple-vision where her friends were concerned. So-and-so was both a very good friend whose friendship and loyalty C. was grateful for, and also someone of whom she would say, after a shopping expedition, “So-and-so can be so dumb sometimes.” If so-and- so said a dumb, dogmatic (liberal) thing about some aspect of race relations, then that’s what it was. But it didn’t make C. any the less willing to be in her company, or any the less aware that so-and-so would come instantly to her aid if she were ever appealed to.

III

A variety of people obviously enjoyed talking with her—a group of Russian tourists on a ship in the Adriatic, our Mexican landlord, our illiterate (in the narrow sense of the word) but intelligent part-time maid in the village, our “uneducated” but quick and bright and morally rock-solid cleaning lady in Halifax, who was in the house when she died, and so on. She disliked coarseness and vulgarity in whatever part of the social spectrum they appeared, but she was free of social and intellectual snobbery. A lot of people came to her memorial service or sent messages of sympathy. A lot of people loved and admired her.

She was almost always on target when it came to the small problems with which I pestered her—what sort of reply should I send to this letter, how much money should I give to this charity, what advice, if any, should I give to this problematic student? People sought her advice about more serious matters, too. She helped save at least one marriage with her attentive listening.

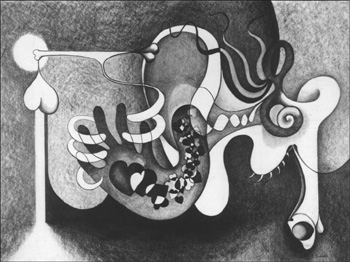

Listening to the Heartbeat, 1974, pencil