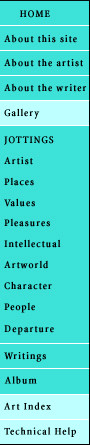

The Great Tree in the Tepoztlán Cemetery, 1982-1986, pencil

Art

I

There was a time when it was fashionable to talk about “risk-taking” art. Maybe it still is.

In the superb drawing that she did during those winter evenings in Ajijic, she took a prodigious risk. She put so much lovingly attentive work into evoking the textures and intertwinings that we could see from our flat roof when we looked into the small back yard next door, with its jammed-together trees and bushes and corrugated-iron shed and henhouse, and into our own garden with its orange tree, lime tree, banana trees, and densely laden avocado tree that rose up above the level of the roof, and then across other rooftops to the ridge of hills.

And then, at the end, she drew in the center of the picture, very prominently, a rooster seen from the side, one of the roosters that strutted and crowed among the hens that scrabbled and fussed around in the yard next door and at times roosted in the tree. (She also did a small painting of a rooster, and said that it was her favourite of the paintings that she did in Ajijic, or at least the one that fully satisfied her.)

That rooster had to be absolutely dead right. The beak, the comb, the tips of the feet all had to be absolutely right, the bird had to be situated absolutely rightly. And, given the texture of the whole drawing, she couldn’t erase and redo without it showing. If something had been wrong, the eye would inevitably have been drawn to it first, or first on subsequent viewings, and the whole drawing would have been undermined, as happens with one of her drawings of a nude in the Seventies, where something is fumbled in the extended left foot—fumbled, as distinct from the bravura distortions of the body in other drawings.

II

She got the rooster right, mercifully. And it has struck me that similar risk-takings go on in a number of her works.

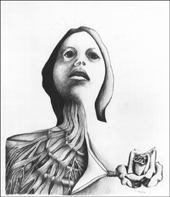

In the drawing of the great tree that appears on the cover of the catalogue of her 1987 drawing show—a tree derived from the huge tree in the Tepoztlán cemetery that she tried sketching on one occasion when her friend the artist Aileen Meagher was staying with us—she put, again, a great deal of work into patiently rendering the intricate branches and roots, and then, at the end, put in a cat standing with arched back and erect tail on one of the lower limbs, and a crouching dog looking up at it with half-open mouth.

The drawing would have been a fine drawing without those being there. But she must have felt that it would have been a bit empty, and she put in those figures that introduced—horrors!—“narrative” into the drawing and risked making it seem, to some, a bit corny.

Other examples of what, if they didn’t work, might be called intrusive elements: the small forest creatures in the final version of Valentine With Love to Christiaan Barnard; the nude in the glove compartment of the vegetation-filled car in The Journey South; the crow on the bare branch outside the window in Major Surgery. I expect there are more.

III

But there’s also a formal aspect to the risk-taking. In a number of pictures, the central object or configuration of objects is at some point, at times more than one point, extended narrowly outwards, so that the eye finally comes to rest, before returning to the central forms and objects, on sharply defined points.

A drawing in which I was especially conscious of this when I visited and revisited the 1977 show is Squash Blossoms. The effect is weakened, indeed virtually lost, in the small reproduction in the drawing catalogue. But when I stood in front of the large work itself, my eye kept moving between the solid but delicately modelled shape of the squash on the right and, by way of the stem, the exquisitely drawn upper blossom on the left, with four or five terminal points, all absolutely right, all there in their precise individuation.

It was as if energies emanating from the bomb-like shape on the right had carried outwards until finally coming to rest at the precise points where the pencil, its task done at that stage, came delicately to rest at the ends of the petals. In my recent conversation with her, C.’s old friend Dorothy Anderson remembered how fond C. was of Dylan Thomas before I came along. I wonder if there wasn’t a faint (or perhaps not so faint) recollection of Thomas’s “The force that through the green fuse drives the flower” at work in C.’s mind when she did that magnificent drawing.

IV

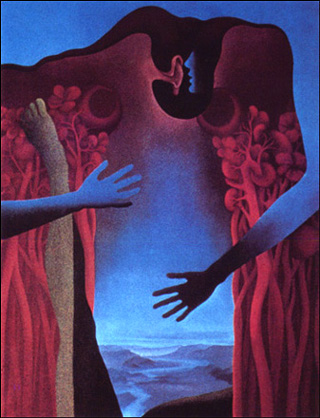

Then there are the dramatic hands, usually with fingers extended, in a number of paintings—the black hand reaching up into the sky in The Garden, the dark red hand in front of the pale-blue deep-space sky in The Solipsist, the hand behind the listening ear in Sanctuary II, the hand holding a pink key against the sky in Salvage, the outflung hand in Head Wound.

There are energies here, the body’s expressive energies, the expressiveness and symbolizing most obvious, perhaps, in the hands of the eight-armed female figure in Ambivalence.

In the central mass, two hands cover or fondle the two breasts, and two are spread protectively (but is it from shame, or a warding off of danger?) over what in a realistic picture, would be the pudendum. But there are also the four outer hands, and it’s a different and more energetic story.

Of the two upper ones, one holds a bouquet, a bride’s bouquet?, of roses, the other is the classic angrily clenched and rebellious fist, the forearm almost vertical, the upper arm stretching out horizontally from the shoulder. At the bottom of the canvas, the hand on the left holds a pair of opened scissors, and the one on the right is discarding a single, perhaps dead, perhaps simply severed, rose.

V

It only now, writing these words, and very belatedly, strikes me that hands mattered a lot to her, a mattering that may have begun, or been intensified, back in those childhood years when she watched her father at work very skillfully on his carpentry, or was allowed to help him with saw and hammer herself.

Hands hold knives and scissors in that painful painting Couple I, both instruments ready to cut. Hands are handcuffed in the even more painful Couple II and in The Guardians. Hands hold keys, make it easier to hear, cover the body protectively, express the body’s anger. Hands hold scalpels and invade the chest cavity in the sinister Major Surgery.

Hands are folded peacefully on top of the monumental, drapery covered, bodyish shape in the drawing Evocation, and on the large, central, egg-like stone, with the sea behind, in the finer drawing Possession. A hand reaches out from the foliage in the drawing Someone, I Think, is in My Tree. The sequence of drawings Morning, Afternoon, Evening are celebrations of the doings of hands and arms detached from visible bodies.

In the exquisite drawing The Geology of Fear, five black hands signal warnings, or blessings, or admonitions in the lightly drawn mass that, with one twist of the eye’s mind, is a convoluted mountain, with another, shrouded figures huddling together.

At the top left corner, however, two more black hands have become a bird that is flying away, presumably to freedom. (It is placed exactly right, as is the drop of honey falling towards the extended tongue in A Taste of Honey—more risks triumphantly taken.) I used to think the drawing was simply a jeu d’esprit. I should have taken the title more seriously. It is a dramatic and very personal work.

VI

More generally, how painful, or at least disquieting some of these works are, for all their superb formal richness and generosity of colour. Figures are watchful, mourn, are bound uncomfortably together, carry a wounded figure through a Vietnam/Rousseau jungle, crouch anxious and naked in a glove compartment, have trouble communicating, perform horror-movie-like operations.

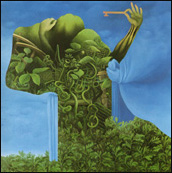

C. always resented, I think, the fact that Mary MacLachlan (who curated the great ten-year retrospective at Dalhousie in 1977) and I, sitting at the dining-room table, persuaded her that the drawing The Revelation was the right thing to put on the cover of the 1977 catalogue. I suspect that, in part, Mary and I were both afraid that a more ingratiating work, such as The Solipsist, would suggest that she was a “pretty” painter. We were wrong, I think, to impose that key-setting image on her. Salvage would probably have been better.

And yet The Revelation is a very powerful and personal drawing. The rose is a beautifully intricate rose, but it is attached to the skin of the young or youngish woman by a wire coil, and it has dragged the skin of the right side of the woman’s neck and the entire right side of her upper body, exposing an intricate system of muscles stretched (or is it flowing or ascending?) over three concentric circles of bone.

Which is to say that the representation of the inside of the body is not anatomically accurate, though meticulously carried out. Which is to say, again, that this isn’t horror-movie stuff.

And what about the woman’s expression?

Well, she isn’t in physical pain, let alone agony, but it is a strange, disturbed expression all the same. If it isn’t agonized, it certainly isn’t joyous. This is not a joyous awakening, it is a disturbing one, and her face registers a disturbed attending or hearkening to—an attempt perhaps to understand—whatever it is that is going on inside her.

The power of beauty is real, the rose must be hearkened to. But beauty is not soft, it is strong, and becoming aware of it, and of one’s own kinship with the rest of the natural world, can alter one permanently. In this picture beauty is a challenge, not a solace. But it is a very important and serious challenge, and here too the title of the drawing should be taken very seriously.

VII

Nature is strange in a lot of these works—strange, powerful, disturbing, wonderful.

In Inland, one of her turning-point works, the incredibly intricate system of interconnected tubes and flowers or flower-like forms is simultaneously plant-like and human, the forms drawn in part from parts of the body. In the Grandparents paintings and the Couple paintings, the figures are inextricably bound together in that way, so that ovaries, for example, are flowers, or vice versa.

The huge opened-up heart out in the woods in Valentine is not only linked by a root-like system to the earth, but is itself, in one of its halves a receding cavern with organic tubing criss-crossing it, and on the other an even deeper cavern or system of caverns leading out into the night sky. The ovaries in The Solipsist are like fruit or flowers crowning a dense cluster of stems, with a natural landscape of hills, rivers, and the sea forming part of the whole Gestalt of body and (self) consciousness.

I don’t think that all this is at all a way of saying, Oh, isn’t it wonderful, we’re all in it together, all part of nature, all part of a single world.

VIII

There may at times, as in Grandparents I, be a rendering of harmony. But even there it should be noted how impersonally strong is the man’s sexual system (the swarming spermatoza in their sac at the bottom linking up with his heart in a penis-like column running up through the center of his body), and how her womb and flowering ovaries are likewise more than merely personal, part of her personality.

Elsewhere, as in the two Couple paintings, the presence of the “natural” makes all the more painful the divisions and alienations represented by the cutting and sundering steel of knives, scissors, saws, and the rigidly manacling handcuffs. Wars go on in “natural” settings, as in Camouflage. But what exactly is the relationship of the men to their environment in that painting, with its echoings both of Rousseau’s innocently celebratory jungle paintings and his war-devastation painting of the symbolic figure astride her galloping horse?

What, for that matter, are the relationships in The Journey South between the hard clear outlines of the car parts (steering wheel, etc), the hand holding the wheel, the abundance of tropical-like vegetation that has invaded the car and turned it into a giant greenhouse, and the naked woman crouching in the glove compartment?

Nature can be trashed, as in Lamentation and Salvage.

In Major Surgery, the chest cavity, the heart in the surgeon’s hand, and the bare trees outside the window all seem lifeless, unmoving, inorganic. The only energies are those of the masked surgeon, looking straight out of the canvas as if caught in the act, and the crow that will eventually fly away. Is the surgeon horror-movie monstrous, another Frankenstein-compulsive researcher? If so, what about the Valentine to Christiaan Barnard? And are all such daring operations things that shouldn’t be done?

IX

We never talked about these aspects of the painting. But I do know that she was fond of Baron Frankenstein as portrayed by the incomparable Peter Cushing, and that she was fascinated by the first of the Quatermass movies (with Brian Donlevy as Dr. Quatermass, and the returned astronaut horrifying taken over by—or taking over—organic things that came his way).

She also, as I say elsewhere, saw the beauty and poignancy of Georges Franju’s Les Yeux sans Visage before I did.

That too is about a doctor, a vivisectionist doctor, whose arrogant confidence in his driving caused the accident that horribly disfigured his daughter, and who is now obsessed with restoring her face, even at the cost of literally stealing, surgically, the faces of other young women. We care so much for his daughter, too, portrayed by Edith Scob behind an unforgettable mask, that we want to believe that it is possible for him to succeed.

But then, Franju, whose Le Sang des Bêtes and Judex she cared for a lot, was a complex figure, like C. herself, and couldn’t simply be reduced to the Surrealism that he, like a lot of intelligent younger Frenchmen—younger in relation to Breton and Co.— had learned a lot from.

X

At least in Head Wound, if one wants to schematize, one can say that the inorganic, the metallic, has triumphed over the organic. But should one—I mean, should one schematize? After all, the dead figures had presumably been a willing driver of that powerful machine, and the highly stylized and simplified presentation of steering-wheel and dash-board makes the machine dramatic and beautiful.

Is that distant, dream-like landscape in Solipsist a true and beautiful perception of depths, or is it an evasion, a substitute for the world of action and dynamic relationships, in keeping with the title?

Mary MacLachlan’s brief introductory essay in the 1977 catalogue is very good.

The Solipsist, 1974, oil