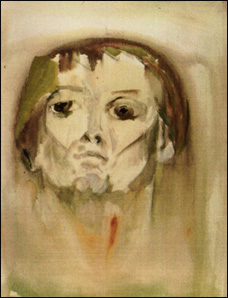

Self-Portrait, [1960], oil

Resistance

I

As a kid, she would “lose” hated glasses, she said. She also, I seem to remember, spoke of hiding a violin in a field on one occasion when she was compelled to take lessons.

She disliked seat belts, locked doors, tight clothing; was exasperated when given parking tickets (sensing, perhaps, that the givers enjoyed giving them); despised what she called “officiousness,” whether of cops, bureaucrats, gallery directors.

She never, I’m sure, followed a recipe or sewing instructions exactly.

But she kept meticulous records of sales, was scrupulous about taxes, documented her works reasonably well, and was a very efficient gallery director.

She disliked having the living room divided from the dining room. I myself grew up in a household where doors were always kept shut.

II

So far as I know, she didn’t keep a journal. Nor are there marginalia in her books—scribbled comments, checkmarks of approval, question marks, underlinings, lines down the sides of passages. Well, a few lines and, here and there, particularly in her book of Wallace Stevens’ poems.

I think she didn’t want to get trapped in self-definitions, including the oblique kind where you underline a passage heavily and say to yourself “That’s ME.” She didn’t really talk about her “self”—analyze herself, brood about her younger self, ask what you thought about this or that aspect of her (“Am I greedy?”, whatever). Perhaps this relates to her early statement to me, “I have no personality but lots of character.” Which of course was a self-defining at that point, but ad hoc and never returned to.

She never talked to me about where or what she had “been” in her art, or explained what she was doing in the present, or talked about where she was planning to go in the future. Nor did I ask.

III

She didn’t dress like An Artist, I mean an artist in my romantic English imaginings. Didn’t dress aesthetically in everyday mode, though she could go gloriously highstyle for formal occasions. Didn’t do harmonious earthtones, organic fabrics, natural leather. Or, contrariwise, “Don’t-mess-with-me” butch. She wore the rattiest old red plaid mackinaw from Forties highschool days for the longest time. It was warm enough, why throw it away? But perhaps a statement was also implied. I wasn’t going to be allowed to make her over entirely.

The nice young vets to whom she took our geriatric pussies on repeated visits were surprised when I mentioned later that she’d been an artist. They hadn’t known.

She may not have looked enough like an artist, I mean an ArtNews Woman Artist, on those two dreadful occasions in the Seventies or Eighties when she tried to find a New York/Toronto gallery. She couldn’t, I think, be intimidating; surround herself with a coded aura of dangerousness.

IV

She used very few jargon terms. No Freudianism, Marxism, victimization-feminism, no appeals to a whole power-charged system, no arsenal of intellectual weaponry. There were terms that we could dip into, especially early on—“ultimate concern,” “appropriation,” “accepted because unacceptable,” no doubt some others that I’ve forgotten—but she didn’t talk in those terms.

I don’t know that I ever heard her use Blake’s phrase “mind-forg’d manacles,” but the poem “London” from which it comes is in one of her undergraduate literature anthologies, and probably it is quoted in The Horse’s Mouth, her favourite novel about art.

I imagine that she got a lot from her months in Göttingen in 1952-53—the lecture-hall explorings by distinguished older Protestant theologians of sin, guilt, duty, personal responsibility, etcetera, in a country where such things had been of the profoundest relevance during the Nazi years; the Nansen House arguings among those German students whom she later called the most impressive group of persons that she had ever known.

This would have been thinking for real, not a mere academic manipulation of abstract terms, or self-serving games-playing and one-upmanship. In the Germany of those years as she was experiencing it, it did not all come down to power in the end, it came down to morality.

I expect she listened more than she talked. I don’t know how good her German became. But it would have been an engaged, a creative listening, and I can imagine intent questions by her from time to time, her eyes shining.

V

She resisted pseudo-moral imperatives like, “Oh you simply have to go to such-and-such a restaurant when you’re in this-or-that city,” not offered as a shorthand way of saying you’d really enjoy the food but because of some idea about the “right” way of being seriously appreciative of food. She didn’t worry about whether she was hearing the “best” recording of a quartet that she loved, as distinct from hearing a performer that she loved, such as Jacqueline du Près. Personally I did worry about such things.

She liked doing things right when it was appropriate, whether preparing a meal for company, or cleaning up afterwards, or getting her bulbs into the ground at the right time in the spring. But I think that this was principally to satisfy herself, and not because of an ongoing anxiety about what others would think.

Justice dictated that the last piece of pie be divided up evenly among her guests, so that’s what she did. Harmony, or do I mean logic? dictated that the different kinds of food on her plate, green veggies, meat, potatoes, etc, disappear evenly in rotation, now three peas, three pieces of potato, three pieces of meat, now two, now…. Which amused her, and which she wouldn’t have dreamed of seeing as an imperative for anyone else.

Such rituals obviously pleased her aesthetically, the formally elegant performance of tasks. Like making sure than when you washed the plates and glasses they were in fact made clean and shining, one by one, and not merely notionally cleaned, in my own kind of sloppy I’m-doing-the-dishes conceptualizing. If you were cleaning a drinking glass, you looked at the glass, you attended to the glass, that particular glass, at that point. And then the next one.

VI

During her final weeks and days, she never talked about her art, never gave any hint about what she hoped would become of her unsold works. I don’t think she had images in her head of how she would like to be perceived in ten or twenty or fifty years’ time. I don’t think she was worried about what would or wouldn’t happen. She very rarely, over the years, talked about the fate of some work of hers in the past.

In the Fifties we had seen Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much in our local movie theatre, the remake with Jimmie Stewart and Doris Day, in which Doris belts out “Que Sera SERA,” a performance that was on all the cafe jukes too.

“Que sera sera,” used lightly, a sort of shrug of the shoulders, was one of those phrases that had entered into our shorthand discourse. Not all working quotations in a mental economy have to come from Shakespeare or the Bible. Or Kierkegaard. Or D.H.Lawrence.

VII

Her favourite novel about art had been Joyce Cary’s The Horse’s Mouth. Did she see something of myself in Gulley Jimson’s young art-groupie Nosey Barbon, stammering with indignation about society’s mistreatment of so distinguished an artist? And in Gulley’s protectrice Coker determined to pin down the rich connoisseur Hickson about the value of Gulley’s paintings. Was there something of herself in Gulley when he denies the possibility of ascribing any absolute value to a work, and refuses to let himself be typecast in the role of victim?

I keep thinking of her as saying or quoting something to the effect that to compare yourself with others is to be no longer free. The exact words would matter here. But I think she meant something like this: that if you let yourself keep comparing your own success or lack of it with that of others you will become trapped in envy or disdain or both, and it will work against your own creativity.

Dawn, 1981–83, oil