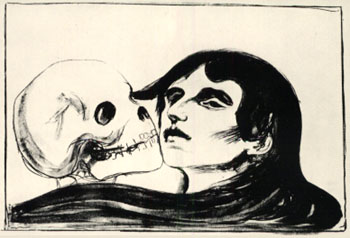

Edvard Munch, The Kiss of Death, 1899

The Expressionist Image [exhibition catalogue], Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1978 [selections]

Introduction

“In their last formulation, great masters always acknowledge the same profound laws of existence.”

Otto Benesch, Rembrandt as a Draughtsman

I

There is no historical beginning to expressionist art, and I hope there will be no end. Hence in discussing the “expressionist image” I am not referring to the movement called Expressionism which existed in Germany during the early part of this century.

Rather, I use the word expressionist as a term to describe a quality which may or may not be present in the art of any people at any time. It refers to the presence of the subjective personality of the artist in the work of art and to certain rather specific forms by which this subjectivity becomes visible.

There are several works by German Expressionist artists in this exhibition, but they are, in my opinion, not more, and sometimes less significantly expressionist that those works created in the less schematized and more personal styles of artists outside the movement.

II

The following passage by J.P. Hodin is a concise and helpful description of expressionist art:

“Expressionism” is in fact a universal style which appears in times of great spiritual tension. Michelangelo’s Rondanini Pièta and the Descent from the Cross in Florence Cathedral both belong to this type of expression, as do the works of El Greco, the aged Rembrandt, the late Goya, Mathias Grünewald, the master of the Isenheim Altar in Colmar, or the artists of the Baroque....

[O]ne of the characteristics is a profound religious emotion. It is a somber, passionate art—the art of Van Gogh, Lovis Corinth, Edvard Munch, Ernst Josephson, the late Turner, James Ensor, Oskar Kokoschka, the painters of Die Brücke, Rouault, the early Chagall, Jack B. Yeats, Soutine, Max Weber, Francis Bacon—in which spiritual experience asserts itself against the tyranny of mathematical thought and technical progress, in fact against the dehumanization and mechanization of culture (Edvard Munch).

III

It is generally thought that to claim such a broad definition for the idea of expressionism renders the term meaningless. However, I feel that it only points up the real need to examine the word and to re-establish its sense and usefulness as a specific, descriptive, aesthetic term.

This is difficult because expressionism is private in intention, elusive, and not easily analysed.

It involves a method whereby imagination and inspiration are acquired through the experience of life and are moulded by the undergoing in isolation of spiritual striving and often great suffering. Fundamental to it is an intense subjectivity at work when interpreting the real world. And although it is without regard for literal representation it is, paradoxically, crucially dependent on reference to people, places, things, and events.

As a vehicle for emotional content the expressionist image is, in the words of one critic, “something not quite idea, not quite feeling but partaking of both, [which] is trying to struggle into articulation” (George Wingfield Digby, Meaning and Symbol in Three Modern Artists).

Such a complex phenomenon cannot be summed up in a few words. But it my hope that this exhibition, the intention of which is to disclose, through the presentation of these expressionist images, some specific forms of that articulation, will make such a summing up unnecessary.

IV

When Rembrandt died in 1669 he unknowingly bequeathed to the expressionist artists of two centuries later a primary source of creative inspiration.

Certainly one finds many very strong expressionist elements much earlier in the anatomical distortions of Grünewald and El Greco, Altdorfer’s primeval and haunted landscapes, the imaginary grotesques of Bosch and Brueghel, and engravings such as Schongauer’s Temptation of St. Anthony and Dürer’s Knight, Death and the Devil.

But it was Rembrandt, and particularly the Rembrandt of the narrative etchings of the Bible stories, who excited the creative imaginations of the modern expressionists.

Vincent Van Gogh, James Ensor, and Georges Rouault all at some point in ther careers copied from these prints. Chaim Soutine and Emile Nolde were likewise inspired by the paintings. And the shy Symbolist Odilon Redon made the statement that Rembrandt was his “favourite artist.”

V

There are several reasons for this situation, but the main one is that the humanism which is so central to expressionist concerns is the same humanism which informs the works of Rembrandt.

Implicit in both the subject matter and the formal elements, it has many visual manifestations, the most important one being Rembrandt’s mastery of light, which he used to illuminate a quality of mind and spirit, as much as he did to create space and form.

Through his expressive use of light he was able to communicate his love of human drama, which led him to develop the technique of etching into a flexible and appropriate medium for his narrative intuitions. He recognized the inherent dramatic power of the black and white image, as well as the spiritual symbolism of light and darkness, and he used them to their fullest capacity when envisioning and depicting the Bible stories.

VI

A second and equally important aspect of Rembrandt’s influence on the 19th-century expressionists was the idea that a work of art was conceived in the medium and must be organically complete in itself.

His driving and typically Dutch appetite for the knowledge of facts, and his inexhaustible supply of vital energy, combined to create a quick and impassioned calligraphic style which enabled him to find a graphic equivalent for everything he saw. The resulting images were sometimes only a few lines or a scribble, but they introduced the modern expressionist concept that a work of art is complete if, in the words of Otto Benesch, “it gives expression to the creator’s full personality.”

For Rembrandt, this entirely spontaneous and personal method soon turned intensely subjective and gave rise to a profound and awe-inspiring pictorial dialogue with the self. Of no other artist are there so many self-portraits as there are of Rembrandt. This self-examination and self-dramatization anticipates the romantic expressionist notion of the artist and hero and martyr by more than two hundred years.

And to complete this picture of a prototypical expressionist life we are reminded, once again by Otto Benesch, that

Rembrandt’s draughtsmanship..., being expression of the creative personality, was too revolutionary to be understood by his contemporaries. Rembrandt is the most striking example of the tragic discord between the artist and his time, so significant for the later centuries of European art (Rembrandt as a Draughtsman).

VII

Doubtless Benesch is referring, in part, to the great 19th-century innovators, Vincent Van Gogh, James Ensor, and Edvard Munch.

These three figures, born within ten years of each other, but of different nationalities and cultures, never met or knew each other’s work in the years before 1890, when Van Gogh died. They created three distinct styles as well as three separate symbolic systems, and yet in spite of their differences they have more in common than not.

Artistic isolation, psychological and spiritual distress, and the compulsion to give it visual form, as well as the intense need to clarify and lend meaning to their lives through their art, are the bonds which hold them together.

In their early work they were all three naturalist-impressionist in intention, and they looked to France in particular for their inspiration. But the Parisian Impressionism of the 1880’s remained too near to the surface of experience and quickly lost its attraction for these spiritually hungry revolutionaries.

However, the plein air artists of a generation earlier, who drew and painted the rustic landscape which surrounded the tiny village of Barbizon near Paris, had developed methods and concepts which were to become seminal to the work of these and other evolving expressionists.

Jean François Millet, The Diggers, 1855–56

VIII

The Barbizon artists, among them Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, Charles Daubigny, Théodore Rousseau, and Jean François Millet, by striving for a plain style and natural vision, sought to eliminate from their art all artifice and pretence. And this, together with Millet’s “Biblical tendencies,” as they were later referred to by Pissarro, supplied a perfect ideological platform for the puritanical passions of the young Van Gogh.

Their unselfconscious abandonment to nature determined, as with Rembrandt, a dynamic and expressive calligraphic drawing style which emphasized their concern for truthful characterization of the fields, trees, rocks, and clouds. It also resulted in their developing graphic techniques that enabled them to represent, by a variety of many small dots and strokes, the different textures of ploughed earth, fields of stubble, or dense foliage.

By the same method the vibrations and dapplings of atmosphere and light became favorite subjects at which they excelled.

IX

Of the group, it was Millet who passed beyond this rather simple form of representation into the expressive and symbolic areas of creativity, and he did it by focusing his imagination on the human condition as embodied in the peasants who worked the land around Barbizon. By seeing the peasant as standing for sincerity, the labor and weariness of life, an unsophisticated fatalism, and the primal and regenerative forces of nature, he expressed symbolically the same humanist feelings which Van Gogh felt for this coal-miners of the Borinage, Kollwitz for her strikers, and Munch for his laborers.

I am certain that he exercised so diverse and profound an influence on Van Gogh because the younger artist recognized the powerful moral and spiritual ideals which they shared, as well as the aesthetic ones. He had not only perceived the “what” and the “how” of Millet’s methods, but he also understood, deep in his creative imagination, Millet’s commitment to self-expression—in other words, the “why.”

He was wholly identifying with him when he quoted in a letter to Theo from the Hague, early in March of 1882, Millet’s statement that “art is a battle—it costs one the skin off one’s back. It is a matter of working like a bunch of Negroes. I would prefer to say nothing rather than express myself poorly.”

X

Millet possessed a great image-making faculty, and through it we can learn about another quite different manifestation of the expressionist image. It is that of the expressive silhouette, which as a formal element depends on the tension created by the restraining and compression of a gesture or gestures by an imposed and simplified shape or contour.

In his prints of The Diggers and The Sower, the compulsions and weariness of labor are expressed by awkward, roughly modeled, and angular shapes and the figures become expressive images because in them shape and contour satisfy emotional ends. There are precedents for this device in the sorrow expressed by the gravity of the heavy rounded shoulders of Mary in Giotto’s Entombment of Jesus, and the misery expressed by the ungracefully humped and scurrying figures of Adam and Eve in Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

As much as the emotional, the idealizing character of the expressive silhouette perfectly suited Van Gogh’s needs when he set out to symbolize human values through portraiture. It also served Edvard Munch extremely well in his woodcuts, where often a rudimentary and subtly artless shape carries a heavy burden of emotional content. And Käthe Kollwitz beautifully adapted it in her expressive graphic images in which people cling together in a unit for human comfort and safety, or a single figure hunches and withdraws into a shape defined by a simple contour.

The artists Honoré Daumier and Georges Rouault combined the expressive silhouette with calligraphy to create energetic works of great dramatic and symbolic gestures, and the symbolist Odilon Redon softened the edges of the silhouette with tonal changes in order to produce his atmospheric and mysterious images of an occult world.

XI

The importance of symbolism in the expressionist image needs to be sufficiently recognized. As a general phenomenon, defined as the use of concrete imagery to stand for abstract, though not necessarily precise, ideas and emotions, it occurs to some degree in all representational art. However, it is the very soul of expressionism, which seeks to use the visible to explain the invisible.

Through symbolic idealization Millet elevated the humble subjects of laborers and peasants, haystacks and muddy fields, from genre to significant expressive content. In doing so he set off yet another example for Van Gogh to act upon.

The Romantic Delacroix symbolized the untamable and ruthless forces of nature in the images of wild animals. Other Romantic artists portrayed madness, war, and natural disaster, especially at sea, as symbolic comment on the human condition. These Romantics were to a large degree responsible for turning the symbolizing activity into the self-conscious process which became the aesthetic basis for the Symbolist movement of the 1880s and 90s.

XII

Symbolism supplied the necessary bridge which enabled Van Gogh, Munch, Ensor, and Gauguin to move beyond Impressionism, which had, because of its concern with surface and the material nature of things, ceased to satisfy their restless and subjective natures. By adapting the aesthetic theory and expressive methods of symbolism they found that they could get beneath the surface of experience.

This moving from physical and objective fact to subjective ideas and feeling was made via a symbol or metaphor which had undergone an intensely subjective reshaping.

Thus Van Gogh distorted the veiled symbolism in Millet’s work to express his own passionate form of Christian humanism. To exorcise their private demons, Munch and Ensor created personal symbolic systems by dramatizing specific objects from their individual experiences and combining them with the more conventional symbols of collective western cultural experiences. In his desperate need to rediscover the sources of the unconscious life-force, Gauguin forced himself to see symbolically through the examples of simplified and distorted primitive sculpture.

Because of this subjective manipulation of the symbol these artists had little connection with the Symbolist movement of the 1880s and 90s, whose strict edicts discouraged distortion and disregard for mimesis.

However, in spite of their conscious escapism and ultra-preciousness, the Symbolist artists Rops, Moreau, Khnopff, Wiertz, and Klinger did create an influential iconographic vocabulary which was used and extended, particularly by Ensor and Munch, for their own expressive ends.

XIII

With their excessive requirements for more and better visual devices to express the knotty emotions of inner experience, it is not surprising that expressionist artists are responsible for the main developments in the techniques of the graphic arts.

Added to their aesthetic needs was the more public desire, especially strong in these zealously communicative personalities, to reach a larger audience with their pictorial ideas than any paintings since could do. The multiple print filled this need and also became an important source of income for many artists, among them Rembrandt and Munch.

XIV

When Rembrandt, the great draughtsman, took up the etching needle it became as natural an extension of his being as his reed pen, and with it he created an art as flexible, varied, and magnificent as that of his drawings. He used the fine etching lines to create every kind of image, from simple, light, and sophisticated ones to the rich dark prints of heavily worked and reworked plates.

Francisco Goya, another genius of drawing and equally famous for the expressive power of his etchings, developed the aquatint technique which made it possible to produce the full range of grey tones in flat areas without the use of lines or calligraphic dots and dashes. In his later years he also mastered the new 19th-century technique of lithography, but it was Daumier who was first to use it extensively for its expressive possibilities. With the lithograph as his soap box, Daumier was able to publish his scathing comments on injustice and his humorous ones on human frailty.

XIV

Daumier, Munch, and Kollwitz used lithography as a means of reproducing drawings. And because of the technical ease of producing a lithograph, the method lent itself to the spontaneous, sometimes playful, other times impassioned use of calligraphic drawing so natural to these artists.

At times the crayon was used flattened, which broadened the line and gave it a painterly quality of rich, varied tones. Redon’s fantastic visions required that he produce blacks which were richer, deeper, and more sonorous than any that had yet been pulled from a lithograph stone. And Rouault, who did everything by a complicated and mysterious method, used photoengraving, etching, and lithography together, or in various combinations, to produce the surface illusion of three dimensions, not unlike an oil painting done in thick impasto paint.

Thus new life was introduced into the traditional methods of print-making and new expressive ends were fulfilled.

Probably the most surprising and triumphant experimentation in the graphic arts was done by Munch when he became interested in the woodcut. Though the technique was five hundred years old he found in it the ideal vehicle for presenting his modern themes, which he often visualized in the form of an expressive silhouette. These large and simple shapes to which the woodblock naturally yields itself monumentalize the otherwise intimate character of his subject matter. And in these prints we have some of the finest expressionist symbols for a psychological condition.

XV

It is easy to understand the present tendency to think of expressionism solely as the purveyor of all that is dark and tragic and miserable; full of bad form and mental kinks, a refuge for the self-indulgent preoccupied with images of nihilism and universal dread. It is easy because it is partly true.

However, in the grip of creative genius bad form becomes innovative form, self-indulgence becomes a dangerous and courageous act of risk-taking, and despair, our modern hell is made credibly visible in symbols and metaphors. This aspect of expressionism can account for many of our most aesthetically important images.

But significant as these images are, they do not tell the whole truth about expressionism. For what is hell without heaven? Melancholy without joy? Despair without ecstacy?

Prone to hyperbole, expressionist artists forever swing between these opposites, and they have also created many works of calm, empyreal beauty. During his most troubled years Munch painted his tranquil and lyrical night landscapes. Ensor, with his wicked sense of humour, lightened his gruesome and somber themes with farce and fantasy. And Rouault’s visionary twilight landscapes and beatific faces of saints are calm and serene. These mystical expressionist images present a balanced concentration of simple forms at peace with the internal structure of spiritual existence.

It was, after all, Van Gogh who advised in a letter to Theo to “Look for light and freedom and do not ponder too deeply over the evil in life.”(Paris, October 1875).

Carol Fraser

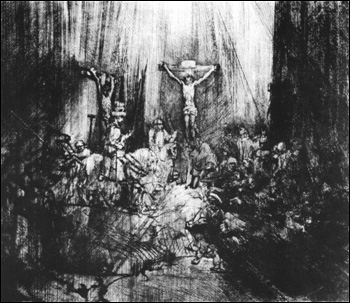

Rembrandt, The Three Crosses, 1660–61

The show consisted of works by thirty-nine artists, almost all selected by Carol from the holdings of the National Gallery of Canada. I have indicated when more than one work was included.

She provided notes on each of them, including the following about Rembrandt’s The Three Crosses:

This magnificent example of Rembrandt’s narrative power, especially in telling the stories of the Bible, is pure expressionism. Intensely subjective and heavy with spiritual and humanist concerns, it has all the qualities of drama and declamation of historically expressionist art. In the unnatural darkness of a false night, a great slash of intense light strikes the central figure of Christ. The tempestuous drawing expresses the restless pressures of a spiritual climax. Everything vibrates. Contours dissolve to reappear as figures in greater fusion with the pictorial atmosphere. Christ, alone and separate, is composed in death, elevated in light.

It is essential to see that the making of this etching, with its bewildering history of changes and stages, was a drama even for Rembrandt. Being entirely imaginary, it is a miraculous document which shows the demanding urgency of the expressionist creative process.

In her prefatory note, Mary Sparling, the then Director of the Gallery, said that the show, which she called “a rare privilege,” would “have been impossible without the generous co-operation of the National Gallery, particularly of its Curator of Drawings, Dr. Mary Taylor and Douglas Druick, Curator of Prints.” To which it can be added that it would have been impossible without the generous supportiveness of Mary Sparling herself.

European

Max Beckmann

Lovis Corinth

Charles Daubigny

Honoré Daumier

Eugène Delacroiz

Alexander Gabriel Descamps

Narcisse Diaz de la Peña

James Ensor (2)

Paul Gauguin

Francisco Goya

Erich Heckel (3)

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Max Klinger (2)

Käthe Kollwitz (2)

Jean François Millet (3)

Edward Munch (2)

Emile Nolde (2)

Max Pechstein

Odilon Redon (3)

Rembrandt van Rijn (2)

Alfred Rethel

Felicien Rops

Georges Rouault (7)

Egon Schiele

Karl Schmidt-Rotluff

Graham Sutherland

Vincent van Gogh

Canadian

Robert Annand

David Blackwood (2)

Bruno Bonak (3)

Fritz Brandtner

Miller Brittain

Frank Carmichael

Dorothy Knowles

Malcolm H. Myers

Jack Nichols

Heidi Oberheide

Donald Otto Rogers

James Shirley

The following statement introduces the brief and relatively perfunctory section on North American (in effect, Canadian) artists, whose works were displayed in a separate area of the gallery, and which had not been part of the original concept of the show.

In North America the expressionist tradition follows a rather precarious path. The pitfalls and barriers to be encountered in Canada and the United States by any activity so exclusively self-oriented have proven to be even deeper and higher than those of 19th-century Europe.

With few exceptions, up until the past three decades the major artists of North America have been motivated by formalist or naturalist considerations. And the history of North American styles is characterized by an emphasis on the objective and realistic. There are a number of explanations for this, the most obvious ones being that our puritan ethic could never tolerate the emotional excesses and self-indulgences of the expressionist mode, and that our industrial and materialistic culture is inimical to the humanism of the expressionist spirit.

However, outside the major trends, which flourish in large urban centers, individual artists in relative isolation are still going about the timeless business of discovering their own subjectivity and the means to express it. It is in their work, which is often influenced by European styles, that the expressionist image appears..

Included in this exhibition are ten Canadian artists and two from the United States. Their prints and drawings offer, through a surprising variety of media and expressive forms, examples of spiritual content and religious themes, humanist concerns, self-examination, and symbolic and expressive portraiture and landscape.

David Blackwood, Capt. Ed Bishop with officers on the Bridge of SS Eagle, 1968