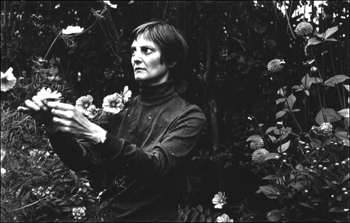

1968. Photo JF.

“Being-an-Artist”

I

When we were in Minnesota, C. simply was an artist, as were her fellow MFA students. They spent long hours in their studios, thought about art, looked at art, talked about art, lived art. They also cleaned themselves up when they weren’t at work, or at least the ones that I knew did. They were not bohemians. Or if they were, it was in the informal manner of our own life on 14th Avenue, in a low-rent apartment that C. had made perfectly comfortable, and that suited us very well.

Halifax was not easy for her. When we first came here and lived in our top-floor apartment on Queen Street, we were able for awhile to keep some Minneapolis patterns going. The apartment was bigger than our one on 14th Avenue in Minneapolis, but it felt similar. The 14th Avenue one had had cockroaches, this one had bedbugs. Both were in shabby buildings only a minute away from a community of stores. She had a studio in the apartment in which she did not have to worry about splashing paint around. She often worked until one or two in the morning.

However, she also had to function as a faculty wife at a decorous university, in a very snobbish town, where Queen Street was emphatically not a desirable address. She dutifully went to teas, joined the Dalhousie Women’s Club, attended talks by its members about their travels and hobbies.

She had no standing as an artist, though people looked at her pictures when they were exhibited, and bought some of them.

Art in Nova Scotia at that time was essentially an affair of Sunday painters with a hobby, plus the so-called Peggy’s Cove painters, who earned money with paintings of picturesque coastal scenes. A professional artist was simply an artist who painted paintings that sold. Only Aileen Meagher, Ruth Wainwright, and Gerry Roach had the remotest idea where C. was coming from, and the first two were themselves tagged as lady painters who did art in their spare time.

I think that C.’s double life became increasingly stressful for her.

The Minneapolis apartment had been a very natural one for students to live in, and was located very conveniently right in Dinkytown, the nexus of commercial establishments a block north of campus that catered largely to students. The Queen Street one had bedbugs, which weren’t amusing at all, and was in a slightly slummy neighbourhood, where C. once watched from her window a kicking, screaming, clawing fight between two wives down in the muddy back yard that only ended when the two husbands appeared and dragged the by then half naked women apart. A man in a downstairs apartment drank and would come knocking on our door when I was away. There were disagreeable people in the laundromat.

Personally the apartment suited me just fine. Its proportions and spaces were admirable, it was a comfortable distance, both physically and culturally, away from the campus and the academic community, and it was downtown. I bitterly resented having to leave it and move to what I thought of as the suburbs, and into a house whose spaces were considerably less attractive. But I hadn’t had to put up with the sort of things that C. had.

II

Having a house of her own obviously meant a lot to C. So, I’m sure, did moving away from squalor. She wanted a home that she could do with as she wished, without having to worry about landlords. She also hungered for a garden. I did not understand the strength of these desires, or the symbolic importance of the house.

I was genuinely disturbed by the proportions of the house, a forty- or fifty-year-old wooden frame affair whose front room and hallway should have been three or four feet deeper. There were also so many windows and doorways that there was very little room for manoeuvring when it came to the furniture and decorations. This piece went here, that one went there, and that was that, there was nowhere else for them to go.

From time to time we tried making minor adjustments—a screen here, a bead curtain there, a folding split-bamboo door between dining room and kitchen—but essentially I was unhappy with the house for seventeen years, and C. knew it.

III

However, I didn’t start out to talk about myself. What I am concerned with here is the fact that I think C. may have in some sense gone underground on Oakland Road, in that she was increasingly reluctant to play the game of being-an-artist. She worked very hard out in the studio, but she did not dress like an artist, or parade herself as an artist, or promote her own work. One or two of her women contemporaries promoted themselves endlessly. Their careers were them, or at least the most important thing about them. C. could not talk herself up, or flatter visiting art-bureaucrats. Nor did she want to get into the art-jury business in a big way.

She did in fact serve on one or two local juries, out of a felt obligation to speak for local artists who might otherwise be ignored. But she did not become an Ottawa person serving on prestigious national juries and making profitable contacts. In a way, she may even have banalized herself to some extent—become someone whose garden seemed at times to matter to her as much as her art. I think there may have been some role-playing here—not exactly Stephen Dedalus’ “silence, exile, and cunning” in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, but a sort of stepping sideways where the public art game was concerned.

Partly this was self-defensive. Perhaps it was largely self-defensive. Something that she said a good many times in my hearing, and that I know she meant, was that she despised the growing involvement of Canadian artists in judging one another officially, and the obvious fact that a number of local artists felt that they weren’t truly serious artists if they weren’t on Canada Council and Art Bank juries. She also, I’m pretty certain, felt as did Gulley Jimson—she admired Joyce Cary’s The Horse’s Mouth—that if she started worrying about her own rank and standing with respect to other artists, she would no longer be free to create as she wanted.

I don’t doubt that she would have been pleased to see what I think of as a real recognition of her come. But she couldn’t herself make it come, and her two attempts to find galleries in larger cities went badly. I suspect she didn’t embark on them with a strong conviction of her own worth and an implacable determination to succeed.

IV

She also, in the Eighties and perhaps even the late Seventies, turned away from any strong engagement with the art journals. She said a number of times to me that in fact she hated art, by which she meant not the art of Van Gogh, Brueghel, Redon, and so on, but art as it now currently was. She said that she could go through the journals and find nothing that spoke to her personally, that deeply interested her, that made her want to see more of this person’s work.

Not invariably, of course. She was interested in Anselm Kiefer, I know, and I’m sure there are other names that I have forgotten at the moment. But essentially current North American art had ceased to count for her as a source of refreshment and stimulation.

She said at times that she wished that she had gone into something useful, like nursing, instead of into art. She said that she wouldn’t be sorry to give up art. If her body had been stronger and more to be depended on, she might in fact have tried to get some kind of part-time hospital work in her fifties, if only as a reader and comforter.

Night Garden with Full Moon, 1985, w.c.